In “Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology,” a 2004 essay that is a true joy to read, David Graeber discusses a common critique of anarchism—horizontal and voluntary forms of social organization could never scale up and replace the modern nation state. After an imagined skeptic asks, “Can you name me a single viable example of a society which has existed without a government?” Graeber writes:

The dice are loaded. You can’t win. Because when the skeptic says “society,” what he really means is “state,” even “nation-state.” Since no one is going to produce an example of an anarchist state—that would be a contradiction in terms—what we’re really being asked for is an example of a modern nation-state with the government somehow plucked away: a situation in which the government of Canada, to take a random example, has been overthrown, or for some reason abolished itself, and no new one has taken its place but instead all former Canadian citizens begin to organize themselves into libertarian collectives. Obviously this would never be allowed to happen. In the past, whenever it even looked like it might—here, the Paris commune and Spanish civil war are excellent examples—the politicians running pretty much every state in the vicinity have been willing to put their differences on hold until those trying to bring such a situation about had been rounded up and shot.

Exempting examples like Rojava, which is surviving over a vast region with non-state governance, it’s true that anarchist organizations rarely scale up to the level of a state. But maybe that’s part of the beauty. Maybe state-sized systems that operate at such a huge remove from our daily concerns are part of the problem, and creating something to replace them that operates at that same scale would inevitably replicate many of the problems that make us want to replace them in the first place. And maybe looking for a single something to replace it could get swapped out for a search for many things. Graeber continues:

There is a way out, which is to accept that anarchist forms of organization would not look anything like a state. That they would involve an endless variety of communities, associations, networks, projects, on every conceivable scale, overlapping and intersecting in any way we could imagine, and possibly many that we can’t. Some would be quite local, others global. Perhaps all they would have in common is that none would involve anyone showing up with weapons and telling everyone else to shut up and do what they were told.

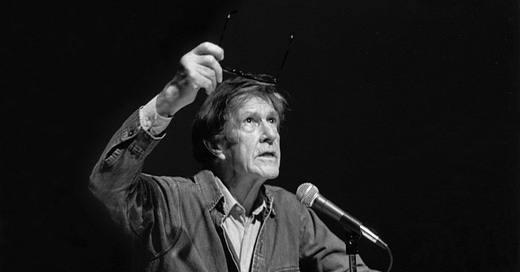

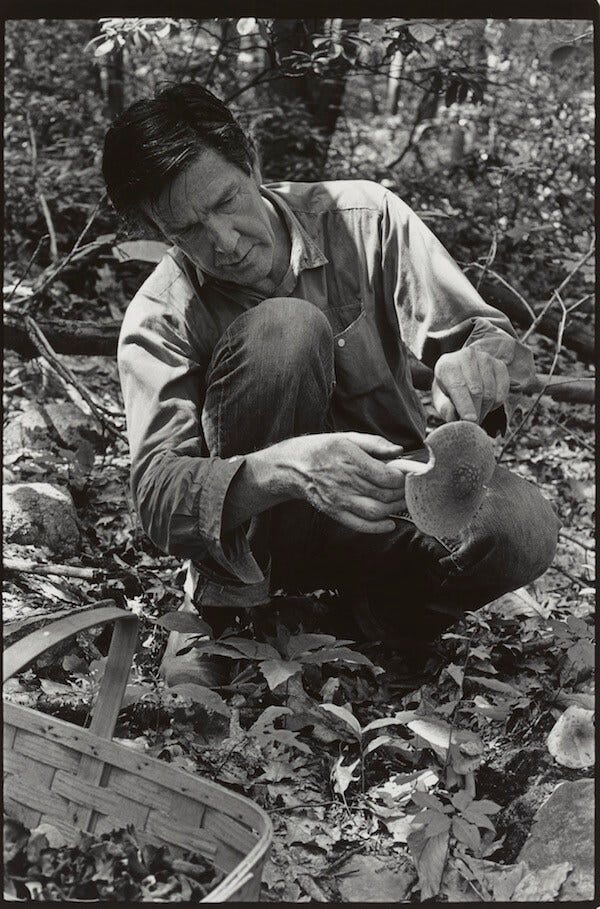

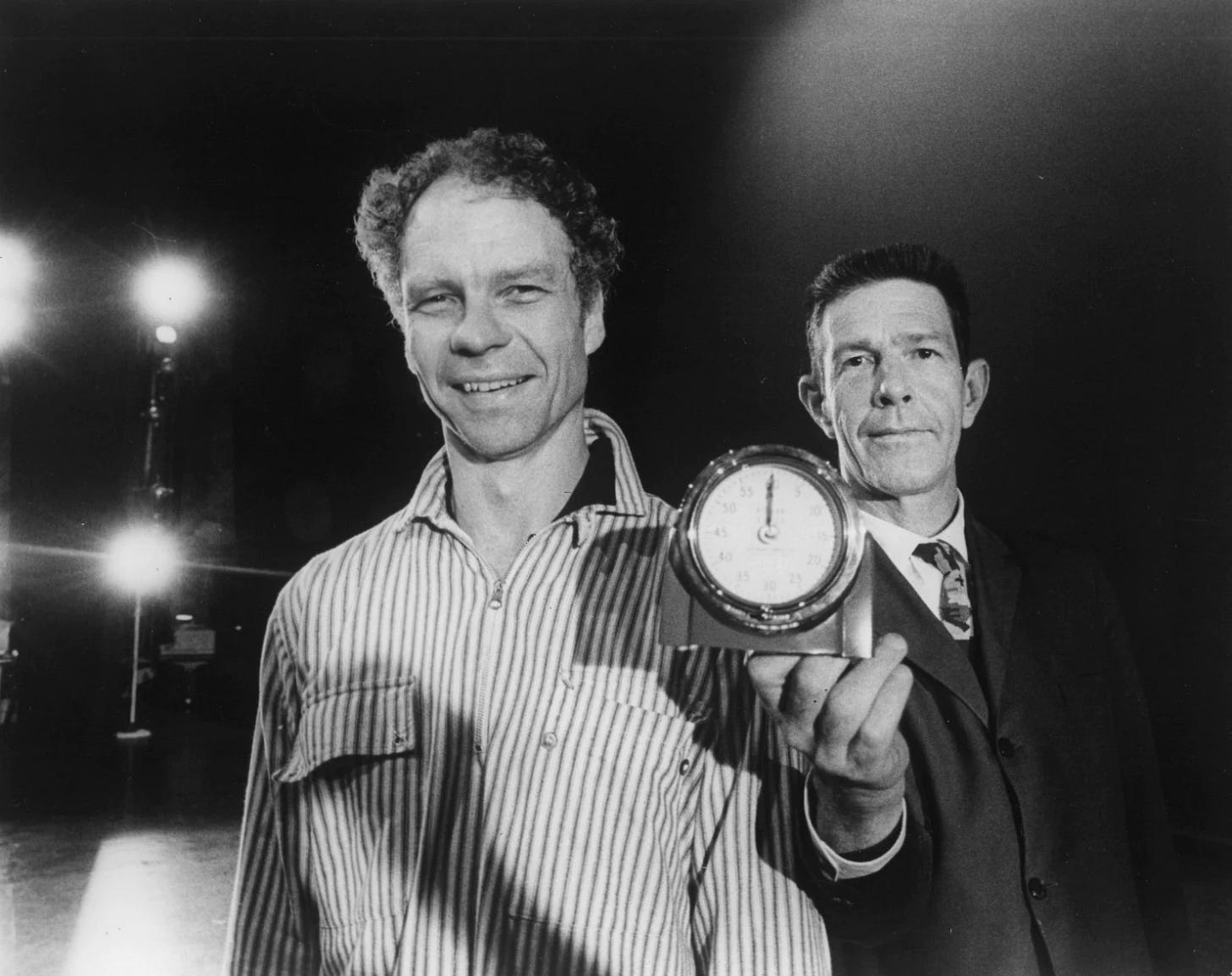

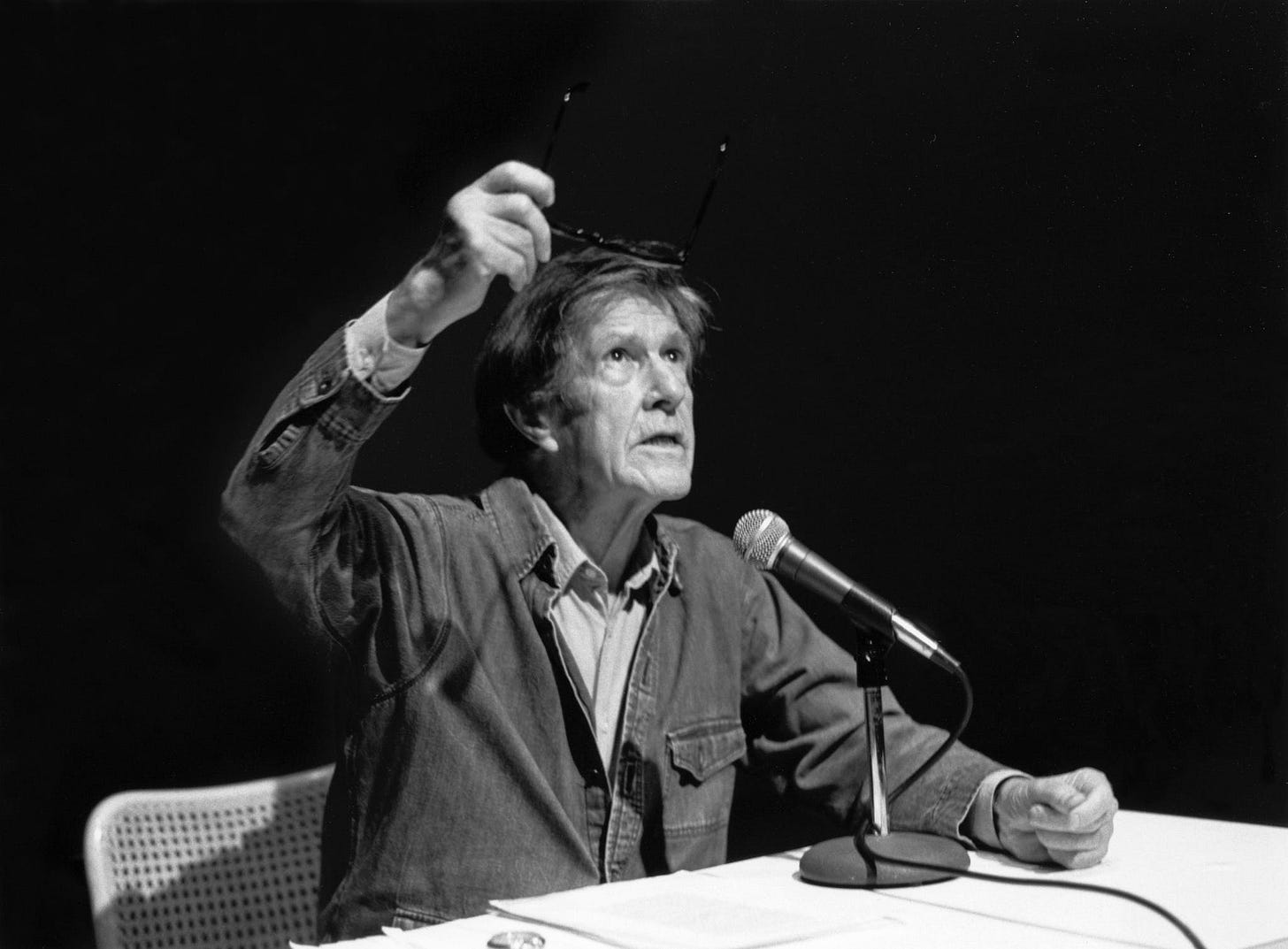

The composer John Cage, in addition to revolutionizing experimental music in the twentieth century, was also an anarchist and a mushroom expert. (One of the first large sums of money he and his personal and creative partner Merce Cunningham used to fund their artistic activities came from Cage’s winnings on an Italian game show where the contestants could choose their topic and answer questions in their area of expertise. Cage chose mushrooms and won the grand prize. They bought a van for tours. Later, Cage and Cunningham made extra money on the side supplying fancy mushrooms to Michelin starred restaurants in Manhattan.) When Cage founded the New York Mycological Society with a number of other mushroom enthusiasts (who were presumably not also anarchist composers), he made sure that the bylaws stipulated that there would be no president and all members would have equal power and an equal say. (NB, I have checked, and Cage’s bylaws have long-since been scrapped.)

The social anarchist vision of a society composed of a commune of communes can be envisioned as “an endless variety of communities, associations, networks, projects, on every conceivable scale, overlapping and intersecting in any way we could imagine, and possibly many that we can’t,” to quote Graeber again. Any organization or association where we can control the terms of how we interact can and should be organized without coercive figures demanding what anyone else can or cannot do. Maybe it’s a mycological society, a bowling league, or a city, but anywhere we can create forms of freedom, we can and should.

One of the best early proponents of anarchism—and one of the most enduringly readable—is Errico Malatesta. When I first encountered that passage from Graeber quoted above, it immediately reminded me of Malatesta’s 1899 essay “Toward Anarchy.” He begins, “It is a general opinion that we, because we call ourselves revolutionists, expect anarchy to come with one stroke—as the immediate result of an insurrection which violently attacks all that which exists and which replaces it with institutions that are really new.” But, Malatesta points out, it would be rather problematic to coerce a world accustomed to coercion into non-coercive social forms. Anarchy will not succeed if we follow Rousseau’s notion that some people will have to be “forced to be free.” As Malatesta writes, anarchy will not succeed until everyone “will not only not want to be commanded but will not want to command; nor will anarchy have succeeded unless they will have understood the advantages of solidarity and know how to organize a plan of social life wherein there will no longer be traces of violence and imposition.”

This brings Malatesta to the pivotal statement in “Toward Anarchy.” He writes, “Therefore, the subject is not whether we accomplish anarchy today, tomorrow, or within ten centuries, but that we walk toward anarchy today, tomorrow, and always.” The revolution is already underway, as long as we realize and remember, along with Malatesta, that we want a “society based on free and voluntary accord—a society in which no one can force his wishes on another and in which everyone can do as he pleases and together all will voluntarily contribute to the well-being of the community,” and then organize everything we can control with that aim in mind, and then seek to take control of more and more. Take care of each other without turning it into a business. Practice mutual aid so that we won’t require the largesse of billionaires or states. Provide for each other without asking if someone has deserved or earned it. We all, by virtue of being alive, deserve what it takes to stay that way. And maybe, like John Cage writing the bylaws for the New York Mycological society, we can recognize that our hobbies don’t really need a president.

Various experiments in social transformation can overlap and coexist or never have anything to do with each other and all still contribute to changing our understanding of what’s possible and how we can live. They can be vast in scope or very small. We can rethink a whole city or our book club with a half dozen friends. Every attempt to do anything without coercion or hierarchy is part of the whole process of building the new society in the shell of the old.

This brings me to a few notes on Murray Bookchin’s 1995 book Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm. Bookchin calls the sort of performative, politically impotent anarchism of crusty punks and other subcultural groups “lifestyle anarchism.” Lifestylists tend to be dropout artists who act as the first stage of gentrification rather than actually improving the lives of the marginalized groups in the neighborhoods they move to. By rejecting society and living on the margins, lifestylists don’t challenge the existing order, but let it be. The world grinds on, crushing the poor and what remains of the natural world, but the lifestylists settle into a small oasis where they can live their transgressive little lifestyles in peace. Bookchin contrasts this with social anarchism. Social anarchists are interested in confronting power for a total transformation of the social order. They seek to build the new society by directly confronting the current one. Powerful people won’t stop crushing the poor and the natural world until we put a stop to it. Dropping out of society won’t help.

Before I get too far into what an incredible oversimplification this is, I should note that few thinkers have had a larger impact on me than Murray Bookchin. Most of the good ideas I’ve ever had, I later found he had written about much more cogently decades before they ever crossed my mind. The rest of my good ideas I stole from him. That’s something of an exaggeration, but the point is this: I’m not one of those people who loves getting on the Internet to talk shit about Murray Bookchin. They are legion. They are annoying. And I’d hate to join their chorus.

But here I go. As overblown caricatures of certain tendencies, the distinction between lifestyle anarchism and social anarchism can be useful. But very few people are entirely one or the other. There is no chasm, so we don’t need to worry about whether we can build a bridge or not. The space between these tendencies is more like a crack in a sidewalk than a chasm, and most people will cross from one side to the other without even realizing it’s there. I have known a lot of “white anarchist punk kids” (and maybe even been one), living on the margins and going to basement shows. But in addition to this “lifestyle,” so many of the people I knew in that world were on the frontlines of organizing protests and taking the teargas, as well as building community gardens, mutual aid organizations, info shops, free teach-ins with street medics, and on and on, successfully combining a dropout lifestyle and more overtly social anarchist activities. You can help shut down the streets at a G8 conference and then come home and host a noise show in your attic. Lifestylist activities are easily combined with more obviously political tactics. We all contain multitudes and can do an incredible variety of things with our time.

Moreover, given what I quoted from Graeber and Malatesta above, there is value in viewing purely lifestylist activities as also worthwhile, rather than some cowardly retreat from what really needs to get done. I said revolutionizing your book club and your municipality were both part of the same process. We won’t transform our social order until we start transforming how we think about what’s possible, but it’s hard to get people to start thinking differently about the world until we start changing it. Both the personal and the political need to change, and neither set of changes will get very far without the other. In my example above about shutting down a G8 conference and then having a few dozen people over to watch a performance only a few dozen people might enjoy, it’s best not to think of the music as a break from the “real” work of fighting imperialism, but more as another activity that can contribute to a world where we all have the resources to do what makes us happy and no one is bossing anyone around.

My own radicalization happened through punk rock. When I first encountered loud, fast, aggressive music, I found it very thrilling, just on a purely musical level. My older brother’s classmate was the drummer and vocalist in one of Wisconsin’s all-time great punk bands. He started giving my brother his old issues of Maximum Rock ‘n’ Roll back in its golden age, and I read the columns and encountered all sorts of leftist ideas tied to this loud lifestyle I loved. And then I really started to think new thoughts. I was so inspired by all the references to anarchism that I read the encyclopedia entry on the subject some nine or ten million times, and then put myself on high alert for books by this Kropotkin guy. This was before the Internet or ordering books on it, and I had no idea what interlibrary loan was, so my mission remained a failure for several years. Despite my inability to get my hands on any anarchist theory, I unwittingly got some practice. By attending and playing underground punk shows, I experienced a DIY world that existed without the permission or blessing of the mainstream culture industry. And I experienced it on a very visceral and practical level. Kids just like me booked the shows, put them on in any available space (the show linked in this paragraph was in a bowling alley), recorded each other, and then promoted those records in each other’s self-published zines.

At extended family gatherings, someone inevitably asks me something like, ‘How long do you plan to do this music stuff if you probably aren’t going to be successful?’ To outsiders of this subcultural milieu, it seems like if you’re playing in bands and you’re not in the running for a Grammy, you obviously aren’t successful, so you might as well turn it into some avocational hobby where you maybe play some Eagles covers in the basement with your buddies every once in a while and talk about what coulda been. But there is a whole world of cultural creation out there where people just like us take matters into our own hands and make things that means something to us, and then disseminate it in ways that make everyone involved feel welcome and included. Ideally, anyways. When I first started playing music, I did it because I enjoyed playing music with my friends and in front of people. That was my goal. So the first time I went to band practice, I was already successful. I had set out to play music, and then I had. There is a lesson in doing this that no amount of political theory can teach. How do you find your people and do your thing? How do you work together to realize one another’s visions? If it’s just us, and no one is making us do this, what will we do, and how will we do it? We’ve given ourselves total freedom, so now what?

It's easy to critique the political efficacy of all this in the same terms Bookchin used in Social Anarchism or Lifestyle Anarchism: An Unbridgeable Chasm. The world of punk and experimental music is more of a subculture than a counterculture. It’s doesn’t confront the existing order as much as it acts as the minor leagues for the mainstream. Bands produce cultural commodities and try to sell them. It’s the same process, just small scale. It’s still all about the creation and sale of commodities. A touring musician is like some unholy combination of a medieval troubadour and a traveling salesperson. Sing a song and then peddle your wares. And drive your gas guzzling van on the interstate to get there. It’s the same business model as the mainstream culture industry, just with way lower stakes. But at the same time, taking control over every aspect of the creation and distribution of your work is a worthwhile exercise in refusing the given. As a political act, it certainly “isn’t enough.” And it could easily get dismissed as lifestylist. But experiencing that world has changed more hearts and minds than just mine, and put many, many people on the path to real political opposition.

There is no chasm to bridge, just a world to transform. There are as many ways and scales to work toward that goal as there are human activities. We can realize our goals right now in any way we can. The revolution is already underway.

I’ll close by returning to Graeber and Malatesta. Near the end of the section of “Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology” I’ve been quoting from, Graeber writes that change “will necessarily be gradual, the creation of alternative forms of organization on a world scale, new forms of communication, new, less alienated ways of organizing life, which will, eventually, make currently existing forms of power seem stupid and beside the point. That in turn would mean that there are endless examples of viable anarchism: pretty much any form of organization would count as one, so long as it was not imposed by some higher authority, from a klezmer band to the international postal service.” Almost as a temporally reversed response, Malatesta writes, “Therefore, the subject is not whether we accomplish anarchy today, tomorrow, or within ten centuries, but that we walk toward anarchy today, tomorrow, and always.”